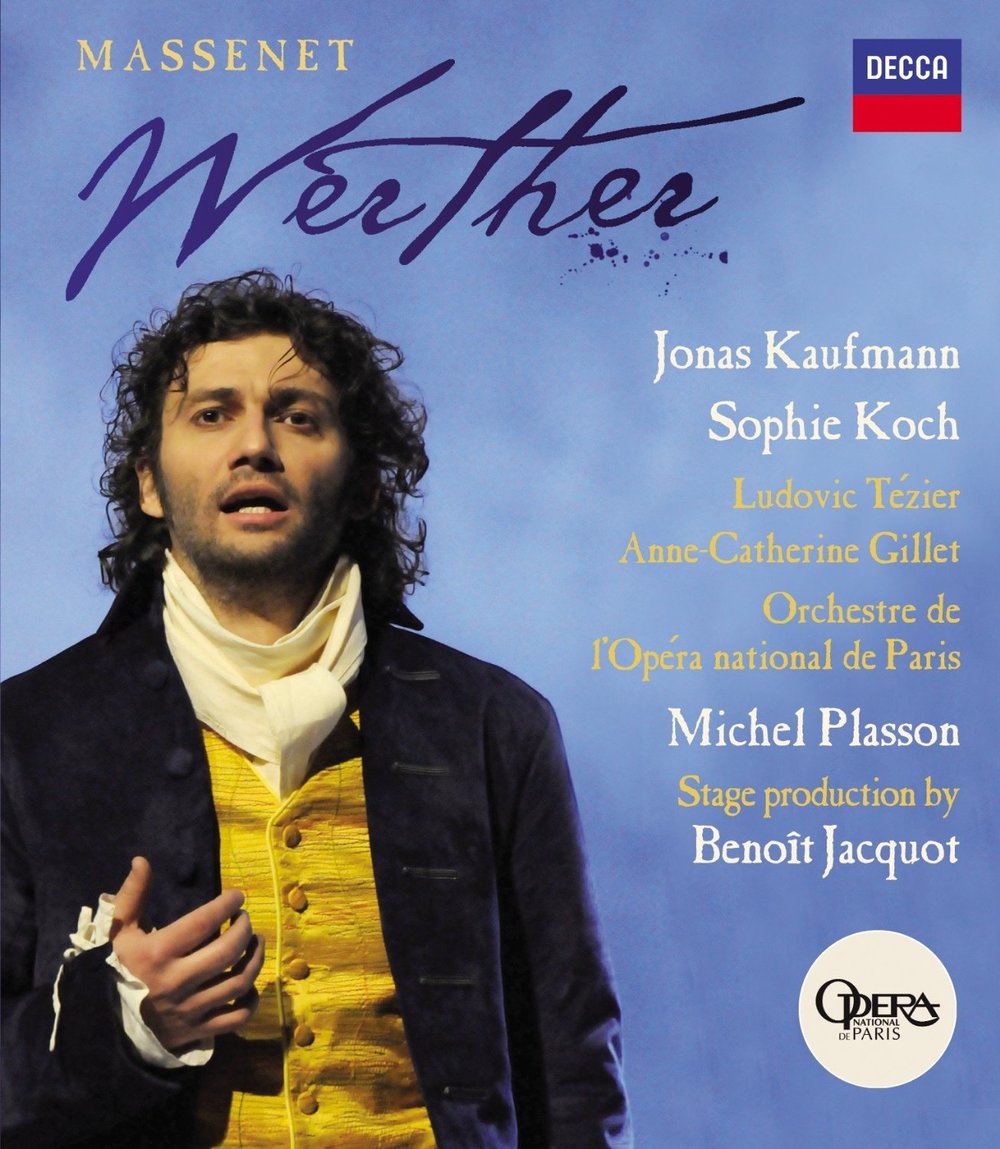

Massenet 💓 Werther opera to a libretto by Édouard Blau, Paul Milliet, and Georges Hartmann. Directed 2010 by Benoît Jacquot at the Paris Opera Bastille. Stars Jonas Kaufmann (Werther), Sophie Koch (Charlotte), Ludovic Tézier (Albert), Anne-Catherine Gillet (Sophie), Alain Vernhes (Le Bailli), Andreas Jäggi (Schmidt), Christian Tréguier (Johann), Alexandre Duhamel (Brühlmann),and Olivia Doray (Käthchen). Sung in French. Michel Plasson conducts the Orchestre de l'Opéra National de Paris and the Maîtrese des Hauts-de-Seine (Chœur d'enfants de l'Opéra National de Paris). Set design and lighting by Charles Edwards and André Diot; costume design by Christian Gase. Directed for TV by Benoît Jacquot and Louise Narboni. Released 2014, disc has 5.0 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+ (but with a warning from John Aitken noted at the end of the review)

This version of Werther was originally created at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 2004. It was performed at the Bastille in 2010; shortly thereafter it was released in a very successful DVD. So it's great now to get it in HDVD.

Werther is a huge, long workout for two singers (Werther and Charlotte) with two modest supporting roles (Albert and Sophie) and a few extra singers for local color. The third star after Werther and Charlotte is the orchestra, constantly providing Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) to give the over-worked tenor and mezzo some breathing room. So it was appropriate for Benoît Jacquot and Louise Narboni to show the orchestra in the video numerous times in views similar to our first screenshot below. I can't remember any other opera video that comes close to giving the orchestra so much attention. The video picture here looks a bit dark; but in my HT, the orchestra shots were all enjoyable:

Stage director Jacquot also took charge of the video, which he directed with the help of Louise Narboni. Jacquot's goal was not to make a video record of what the theater audience experienced. Jacquot was well aware of the futility of trying to do that with today's recording technologies. Instead, he set out to create an alternate experience for the home theater viewer that would take advantage of things the video team can show the home viewer that the theater audience cannot see. The same director prepared two products: (1) an opera at the Bastille and (2) an opera film for my home theater!

This is the only opera video I know of where this has been tried. Even François Roussillon (today's leading fine-arts videographer who often worms his way into producing/directing roles) has never gone this far. For Jacquot (and Narboni), making a great video for me was just as important as staging a great show for the Bastille audience.

So what is different about this video to make it so different from the the norm? First, the director repeatedly shows us at home what is going on behind the stage as well as in the orchestra pit. Second, although we get all the whole-stage shots we need, the director puts us much or most of the time somewhere between 10 feet and 10 inches away from the singers. Third, the singers are required to act exactly as they would act in real life in the situations depicted. (Finally, instead of talking, they have to sing exhausting amounts of difficult music; but this is not different from the norm.)

Let's look again at behind-the-scenes views Jacquot mixes in with the stage performance. Here, for example, is a silhouette shot of Charlotte (Sophie Koch) doing exercises while waiting to go on stage:

And here we see Charlotte's father and two of his friends on stage as well as the backs of children getting ready to rush forward on cue. Note the slope of the stage and the tiny TV monitor in top center:

And here we see both the front and back of the garden wall set. I've never seen before such frequent violations of the separation of what is illusion and what is real in a theater production. But it doesn't distract at all from my enjoyment of the drama:

In the picture above, we see Charlotte, age 20, in the white dress surrounded by her father, the local Bailli (or Baliff), and his 7 younger children. Their mother died, and Charlotte is taking on the role of rearing them. Charlotte is engaged to be married to Albert, who is away on business. The family has recently met Werther (Jonas Kaufmann), a newcomer to the village who is seeking a civil service post with the local Prince. Werther, pious and honorable, is enchanted by village life in the spring, and he sings romantic praises of nature and the sun:

The annual Wetzlar "Friends and Relations" ball is taking place. Because Albert is out of town, Charlotte has no escort. Werther is recruited to appear with Charlotte. The townspeople will understand that Werther is with Charlotte merely to show his gratitude to all the citizens for their hospitality to him. Well, Werther sees things a bit differently because nobody has told him that Charlotte is spoken for. Before the ball, Werther is impressed to see how beautifully Charlotte is taking care of the children:

Charlotte introduces Werther to sister Sophie, age 15, who will watch the children while Charlotte is at the ball:

It's love at first sight for Werther, and Charlotte is not far behind. Now they return from the ball and are together in the moonlit garden. To surging music from the pit and in the most gallant terms possible, Werther declares his love. Only after that does he learn that Charlotte has sworn to her dying mother to marry Albert:

Time for a bit of relief watching the antics of Johann (Christian Tréguier), a friendly local drunk:

Albert (Ludovic Tézier) returned and married Charlotte. But he is baffled by her frigidity:

"I hope I have made you . . .:

While Albert ponders, Werther suffers. Below, my friends, is a portrait of Sehnsucht ("longing"), the essence of German romanticism. Sehnsucht is the inextinguishable desire to possess the unobtainable; the thirst that can be quenched only by death. Note the long wall of Sehnsucht in this image, a wall that overwhelms the individual and extends into infinity:

Albert perceives that the problem with Charlotte is Werther. In the most circumspect and noble terms possible, Albert cautions Werther not to interfere with his marriage and Werther promises he will not. Albert says, "We all look for love, and behold, perhaps it passes our way."

Now Sophie has also fallen for Werther! She's not quite old enough to see what is happening to the older members of her circle. But she is old enough to feel the delirium of first love:

Everybody is miserable except Sophie:

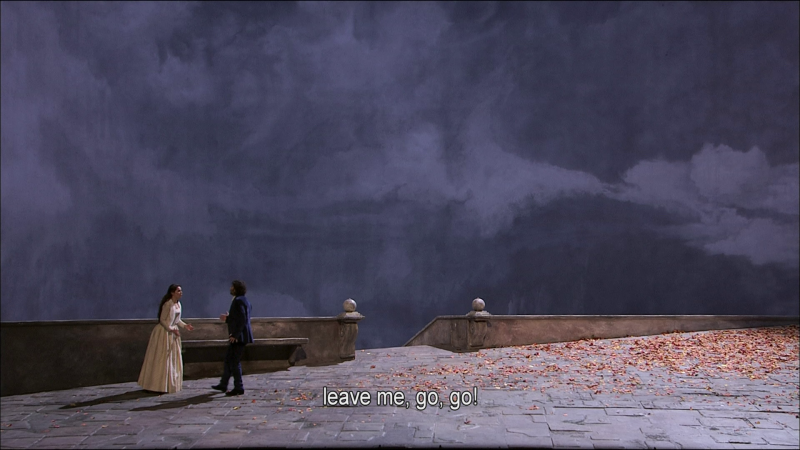

Charlotte asks Werther to leave, at least until Christmas. She hopes she can forget him and return to loving her husband:

Poor Sophie thinks that she has somehow run Werther away:

But to Sehnsucht, the diameter of the earth is no further than are whispering lips from a lover's ear. Werther sends Charlotte letters in which he says he is "always alone." Note the outsized, gloomy drawing-room set that underscores Charlotte's isolation and loneliness. And since Jacquot and Narboni are making a movie out of this, why not show Charlotte from above to further drive home the point:

But Charlotte is honorable and resolute:

And then it's Christmas, and Werther is back:

Werther sends a message to Albert: "I'm going on a long journey. Would you lent me your pistols?"?

This gets us to Act 4, and I'll stop. It's such a simple story, but the glory is in the telling. Here's how Jacquot himself describes this, quoted from the keepcase booklet:

“When I make a film, for me the whole thing stems from the actors who are going to inhabit it. I followed the same principle when I created this production of Werther: the aim of all the gestures, pacing and blocking, momentum, repose, sets, costumes, and lighting was to give the singers the sort of presence that makes it impossible not to believe what they are expressing, just as they truly believe what they are singing. In any case, these wonderful singers are also excellent actors, interpreters of a music that, quite apart from its subtleties, asked for the simple, uncluttered truth, in all its pathos. It is for you to hear, and to see.”

Of the 28 screenshots in this review, 4 show events off-stage and 18 show head and shoulders. Only 6 shots show something from an audience perspective. The Paris Opera put together a faultless cast, most of whom are native speakers of French. Their singing is as wonderful as Jacquot states; and, although I'm a poor judge of this, I think the French diction is excellent. My close-up shots demonstrate how capable the singers are as actors.

The opera is based on a landmark work of European literature. I would venture to say that the nobility of the libretto and magnificence of Massenet's orchestral and vocal scores make this his greatest opera as well as one of the greatest operas in French.

Many readers of this website live where they can rarely (or perhaps never) see live Western opera, but most of them have seen many movies. These viewers would likely accept Jacquot's decision to make a movie of this. For them, there is nothing to say as to how to improve this title, and it would get an "A+" grade.

But as you can see from a comment (slightly edited) below by John Aitken, other viewers, especially those lucky folks who can regularly attend live opera, may well find all of Jacquot's movie-like close-ups both distracting and distressing. They prefer to see long-range and whole-stage views that remind them of their experiences in viewing opera in real theaters. For them the correct grade for this Werther would be in the "C" to "B" range.

To serve the largest possible audience, I'll go with the "A+." But more seasoned viewers will appreciate the warning about this from John Aitken.

Finally, here are some video samples for you to consider, all focusing on Kaufmann:

OR

PS by Henry McFadyen Jr.

I think often about the Jacquot and Narboni movie-like Werther opera production. I almost feel as if I knew a man who killed himself over love. I think you could make a splendid motion picture version of the Massenet Werther, but that would cost a lot of money and the market might not justify it.

Now, about face! I just read an article in Opera News (December 2016 at page 20) by Royce Vavrek, who recently wrote the libretto for an opera version of a famous movie, and I thought of Werther again. Let me explain.

The famous movie is the Lars von Trier Breaking the Waves, and the new opera has the exact same name with music by Missy Mazzoli and the same general story line distilled in Vavrek's words. Here's are Vavrek's wonderful comments about going from a movie to the opera stage (slight modifications):

“Perhaps the most exciting challenge was the translation of the close-up. The emotional information remains the same in the film and the opera. But the screen allows for a more internal approach to the delivery, while the opera communicates in a grandly external way. Emily Watson in the film often dominates the full frame in close-ups with her expressions supplying great subtext. But Bess in the opera must communicate to the final row of the opera house — the visual equivalent of an extreme long shot. In the opera, the aria becomes the close-up and the music provides the subtext. In both cases our hearts and imaginations are fully accessed.”

So movies and operas work in different ways. But when making a video of an opera, why can't you ramp up access to the hearts and minds of the audience by combining tasteful closeups with the music? The additional cost is moderate with extra performances for the cameras. And the payoff can be terrific, especially when you consider that long shots with video cameras are quite inferior to what the human eye can discern in a theater.