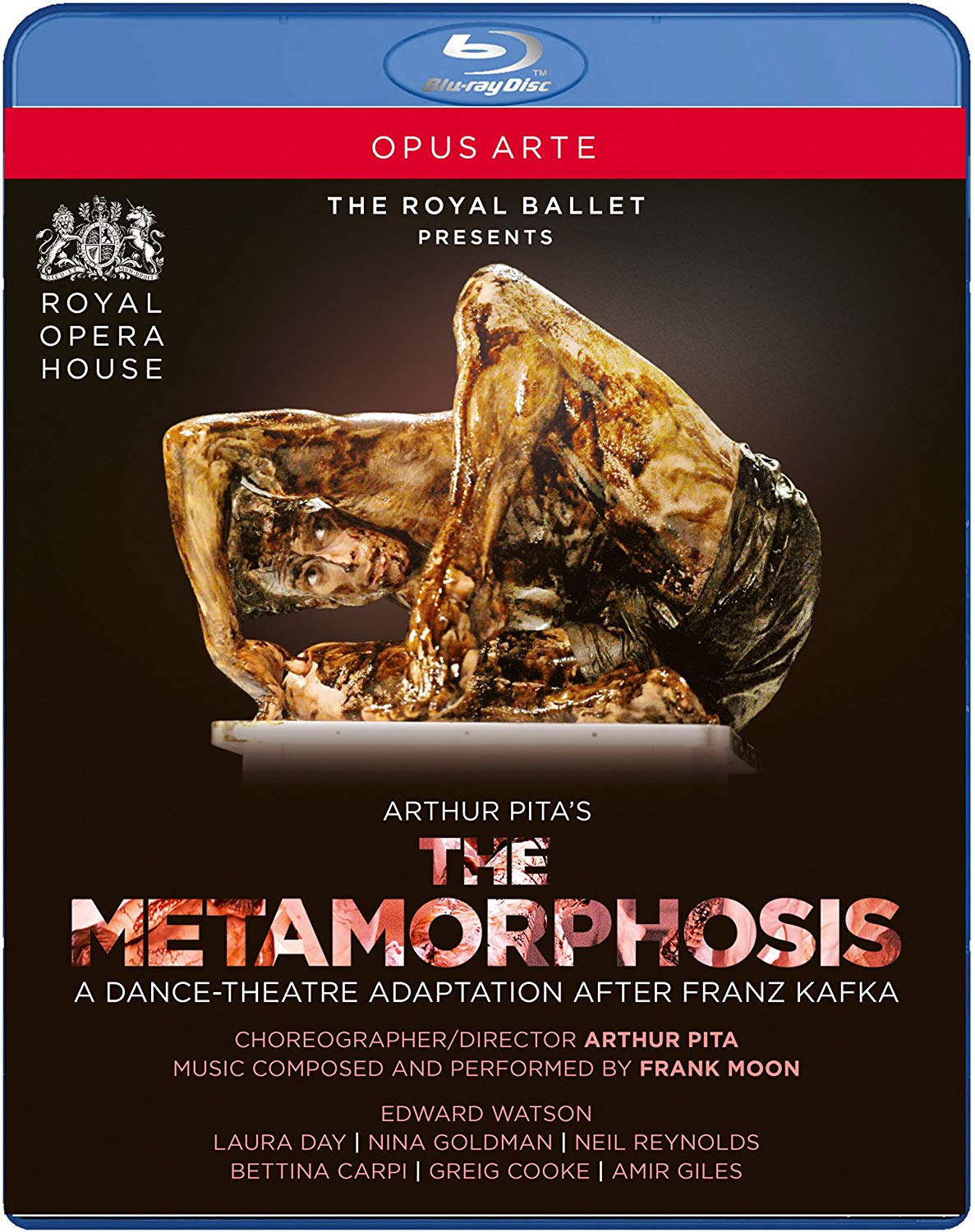

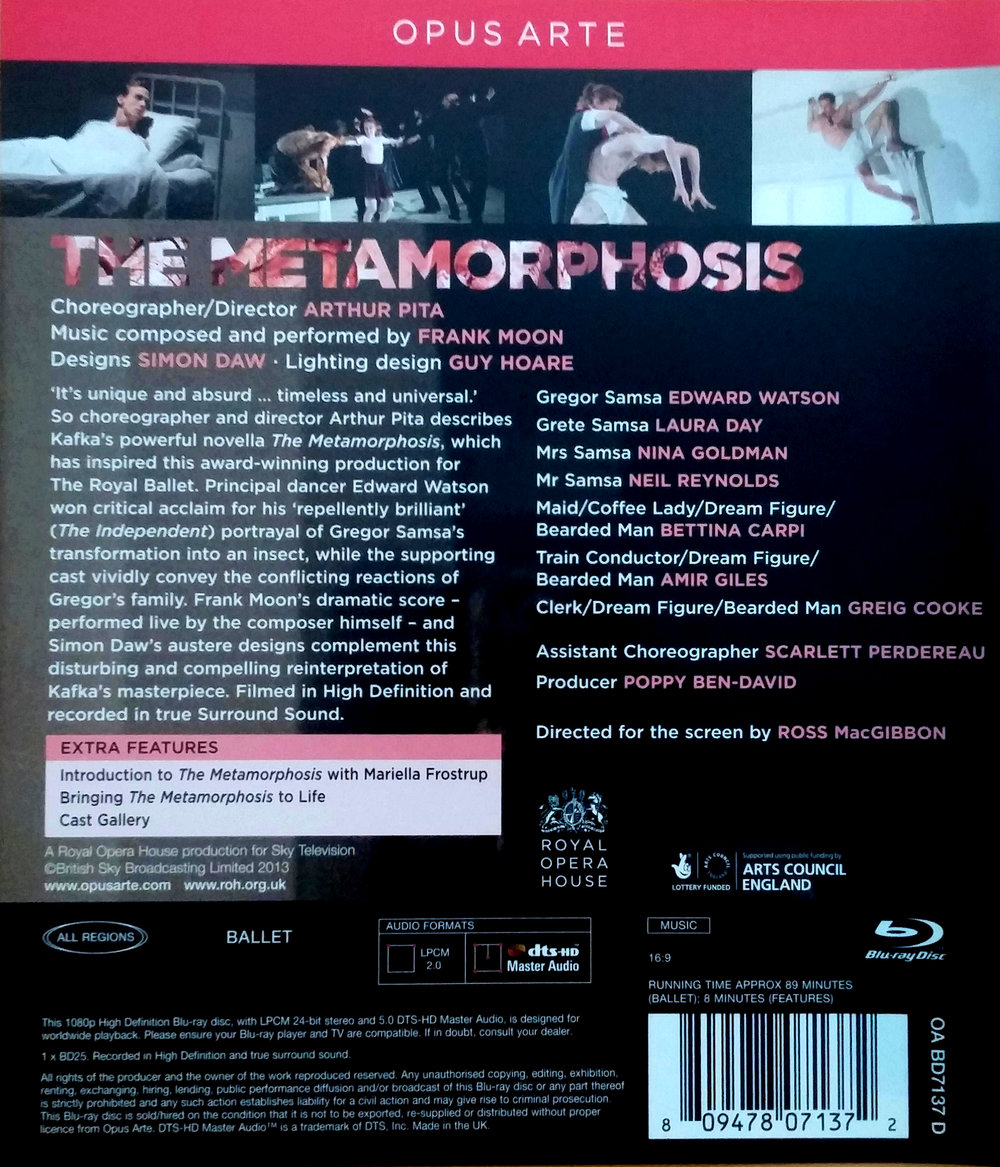

The Metamorphosis, a dance-theater adaptation after the Kafka short story. Choreographed and directed by Arthur Pita especially for Edward Watson, a principal dancer for the Royal Opera House Ballet. Original music composed and performed by Frank Moon, who plays guitar, oud, violin, tam-tam, and sings. Performed 2013 at the Royal Opera House's Linbury Studio Theater (where the work was premiered in 2011). Edward Watson plays the role of the main character, Gregor Samsa. Supporting dancers are Laura Day (Grete Samsa, Gregor's sister), Nina Goldman (Mrs. Samsa, Gregor's mother), Neil Reynolds (Mr. Samsa, Gregor's father), as well as Bettina Carpi (Maid, Coffee Lady, Dream Figure, Bearded Man), Greig Cooke (Train Conductor, Dream Figure, Bearded Man), and Amir Giles (Clerk, Dream Figure, Bearded Man). Designs by Simon Daw; lighting by Guy Hoare. Assistant Choreographer was Scarsett Perdereau. Directed for TV by Ross MacGibbon; Producer was Poppy Ben-David. Disc has extra features named "Introduction to The Metamorphosis" and "Bringing The Metamorphoses to Life." This title is part of the Royal Opera House Collection Series. Released 2014, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A

Kafka's The Metamorphosis Viewed as Humor Literature

The Samsas, a bourgeois, Christian, German-speaking Czech family, lived in Prague about 1910. The family business had failed, leaving the father unemployed and in debt to the new owners. The mother had asthma; the daughter was in high school. The older son, Gregor, went to work for the new business owners as a traveling salesman. Gregor worked hard, was quite successful, and dutifully supported the family to the point that they started to take him for granted, except that Gregor's mom worried that he was burning out his youth in his efforts to maintain the family in its accustomed lifestyle.

The pleasant lifestyle came to an end when one morning Gregor woke up and found that he had turned into a giant cockroach or beetle. (The precise term Kafka used was "ungeheures Ungeziefer" or "monstrous vermin." But as the story unfolds, it's clear that Gregor is a roach-like creature with his semi-hardshell body that easily slips under the sofa and tiny legs and feet with a sticky substance that lets him walk over the walls and the ceiling.)

Gregor continued to have his human mind and emotions, and at first he could even talk a bit. But as time went by he gave up tying to communicate with his family, and he gradually weakened from stress and poor nutrition. The family tried to feed and hide Gregor. But eventually all of them found jobs and dealing with Gregor became increasingly burdensome. The Samsas rented out a room to tenants who left when they discovered the giant cockroach next door. The sister, who was growing up fast, brought the situation to a climax by announcing that Gregor had to go. But the crisis vanished when Gregor conveniently died. With their problem solved, the Samsas found they were more prosperous than ever and that the daughter had blossomed into a beautiful young woman.

How did such a bizarre and slender plot turn into a monument of twentieth-century literature? The answer lies in Kafka's unique voice and style. The voice reflects what Kafka's friend Max Brod depicted (per Wikipedia) as the two core attributes of Kafka as a man: an absolute devotion to truth combined with precise conscientiousness (Kafka made his living as a lawyer who specialized in insurance and workmen's compensation matters). The style is described perfectly by translator Stanly Appelbaum who writes how he finds in Kafka's work a "well-balanced coexistence of detached humor and deep-seated horror." (Kafka's Best Short Stories---A Dual Language Book, Dover, 1997).

I think I missed the humor when I first read The Metamorphosis eons ago as a student. But I just read it again and find myself charmed by the fine sense of irony and humor displayed by Kafka throughout the book. There are other more trenchant and profound things to say about The Metamorphosis. But you don't have to rack your brains to enjoy it. Observers have come up with many explanations for The Metamorphosis. But Appelbaum and I may be among the few to suggest it can be viewed as work of humor.

Arthur Pita's The Metamorphosis as Comedy

How do you make a dance-theater piece about a man turned into a bug? The first challenge is, of course, the actual impossibility of depicting a giant insect. In the book, the Kafka only hints at appearances while he focuses on Gregor's feelings and elaborate deliberations about the situation. But since Gregor can't speak, there is no way for the dance-theater audience to know what Gregor is thinking. Pita had no choice but to change the focus of his play from the monster to the human characters, and he elected to dwell on the humor in the story as much as the horror. And as for portraying the horror, Pita did have the good fortune to know about Edward Watson.

Watson, one of the world's most esteemed ballet dancers, specializes in using his physical flexibility and acting skills to play tortured souls. Watson has appeared in a leading or important supporting role in 8 other HDVD ballet titles featured on this website. (Consult our Search tool to find out more about Ed.)

Here's Watson as Gregor going about on his routine as traveling salesman. He rises early and visits his customers by train. On his way home he passes Cafe Praha (The Prague Cafe) where a side-walk waitress pours him a vodka, his only indulgence:

Mrs. Samsa is played by Nina Goldman, the actress-dancer who plays the role of the Queen in our HDVD of Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake. She is a neurotic hypochondriac who is also a health nut and neat freak (a perfect storm of unhappiness). When she puts on her asthma mask, she looks a bit like an insect herself:

Now we meet Grete, Gregor's sister, played by Laura Day. I'll guess Laura was 19 when she auditioned for Grete and about 22 when this was filmed. She was an fine young dancer at the time, but I think she got the nod for her appearance (perfectly convincing as Greg's sister) and strong stage presence. Turns out she is an excellent actress also who dominates scenes while never over-doing it. Today (2014) she is a member of the corps at the Birmingham Royal Ballet. I know the names of many star dancers; Laura is the only corps member I've ever known of by name:

Finally we meet Mr. Samsa at the meager family supper. Gregor's work keeps the family afloat, but money is tight:

But one day Gregor doesn't go to work, and a clerk from the company checks on him at home. Eventually the family breaks thru the door to his room and encounters a horrible surprise:

Gregor has turned into a monster. Even though Watson was directed to make insect-like moves, he continues to look like a man — a man who has frightening problems somewhat similar to persons afflicted with congenital birth defects, second skeletons, or diseases of the nervous system:

Grete loves her brother dearly. Later Grete enters Gregor's room alone to try to talk to him. She finds him on the wall. So now we know that Pita is asking the audience to view Gregor as an insect:

Gregor desperately wants to communicate, but he can't. His lips are dark because of a mysterious brown fluid that oozes out of his mouth. Kafka mentions the mouth ooze one time in the book, but doesn't return to it. But this gives Pita a brilliant way to pump up the horror element in the theater — he can't really give us an insect, but he can sure give us ooze. In a bonus extra, we learn that the ooze is molasses (or treacle in the UK):

Grete gives Gregor something to drink:

The cleaning lady (Bettina Carpi) arrives. She is perfectly cast to depict the loud, strong, practical woman Kafka describes in the book. She goes right to work ordering Gregor around. The characters talk in this production (especially the cleaning lady) but their voices are blurred so you can't understand anything beyond "coffee," "wine," "vodka," and "good night." (There are no sub-titles.) The screenshot below is from what I call the Gregor/Cleaning Woman pas de deux:

Grete is still trying to communicate with her brother. Her best idea is to play some music. She picks an album by her favorite singer with the cute name of Wanda Slavik ("Wandering Slav"). The album cover is authentic-looking with its cheap design, stock artwork, and tacky photograph of Wanda. If this production had been set a few decades later, Grete could have played The Monster Mash. But Grete did make a good pick: the name of the album is "insecktologie."

Wanda sings schmaltzy ballads. Grete is soon lost in dreams of romance and does a floor dance full of longing and desire. Oddly, her mildly lascivious moves are not too different from some of Gregor's monster motions:

And Gregor has his own dream, a gruesome nightmare, which is too dark for screenshots. But here he is after the dream, in worse condition than ever. (The dream scenes for Grete and Gregor are 100% inspirations from Pita. It's brilliant theater that contrasts the frustration of Gregor's situation to the joy that Grete feels as she matures):

Grete urges her mom to enter Gregor's room. Mom does, and she faints. In the Gregor/Mom pas de deux, Gregor sets out to help her back to the kitchen. This is the first pas de deux I've seen in which one of the partners is unconscious. This amazing scene goes way beyond anything Kafka did for Mom in the book:

Grete is increasingly perturbed by the difficulty of the situation and the impotence of her family to deal with it. Mr. Samsa reaches out to her:

The Grete/Daddy pas de deux follows. Grete is going through a metamorphoses of her own. When we first meet her, she's a silly teen in a tizzy over her first ballet shoes. But now she's dancing like a star, so Pita is telling us that some considerable time has passed with the big roach living in the apartment:

Grete and her parents are unified in their despair. Their patience with Gregor is running short:

To help with the budget, Mr. Samsa posted a "room for rent" advertisement. 3 bearded men (Bettina Carpi, Greig Cooke, and Amir Giles) apply to become tenants. They strike up a friendship with Grete and soon a Honga (Jewish folk dance usually called the "hora" in the US) is underway. It's such a relief for Grete and her parents to have a bit of fun:

Gregor in the next room hears the wild clarinet music and wants to have some fun too:

While the others are dancing in a circle, Gregor sneaks into the kitchen and climbs up on a table:

Grete screams. The bearded men are aghast:

Mr. Samsa must return the rent money. The tenants flee making a spitting motion that, according to a Jewish superstition, wards off influences from some evil thing they have encountered. Grete now takes charge and, in a screaming attack, orders Gregor out of the house:

The ever-gentle and conscientious Gregor wants to accommodate Grete by leaving. But the poor bug doesn't know how to do it. The next day the cleaning woman arrives. She opens the window to let in fresh air:

The cleaning lady is the only one now who still shows compassion for Gregor:

This show was supposed to be a star-vehicle for Watson. But the role of a voiceless insect is too limited for Watson to show what he can do. Yes, he's spectacular writhing about in the molasses. But the effect wears off. You put the disc in the player expecting to get a big emotional impact from Watson's performance; but after the curtain calls you find yourself thinking about Grete. To better see what Watson can do, watch his portrayal of doomed Prince Rudolf in the (true-story) Mayerling.

Now that the window is open, Gregor sees his way out. Roaches can fly, you know:

Gregor is gone. The Samsas put on their best clothes for a memorial service:

Gregor's transformation is complete. And Grete has grown from a brat into a beautiful and confident young woman:

So why could we consider Pita's show a comedy? When we are presented with unexpected and incongruous words, actions, or situations that relate to and reduce a tension in our lives, we react with a laugh and call the event a joke or — if there are enough jokes — a comedy. All of us are apprehensive about dealing with people we don't understand well, especially if they seem threatening. So when we see an uneducated cleaning lady brusquely using her mop and strong back to tuck a giant cockroach into bed, we laugh. We don't want to accidentally offend anyone about their religious beliefs. So when the bearded tenants, probably orthodox Jews, produce their own dance music, liquor bottles, and gleefully toss drinking glasses to their host family, we feel relief and laugh. These are the kind of gentle jokes that Pita and his team weave into their show. And these jokes are consistent in intent and tone with Kafka's humor in the written text. So that's my basis for calling this production a comedy (albeit of the darkest possible shade). There are, I know, other more trenchant and profound ways to view The Metamorphosis, but you don't find them in this title.

Kafka published The Metamorphosis in 1915. He was a German-speaking Jew whose family was part of a thriving Jewish community in Prague. As I pointed out earlier, the Samsa family in the book are Christians. (Christmas is mentioned 3 times and the Samsas cross themselves when Gregor dies.) But I think that Pita portrays the Samsa family as Jews who know how to dance the Honga. Pita's take on this would make sense if set in Czech lands during Kafka's lifetime. But Pita updates to about 1950 (with a primitive black and white TV and LP records). This creates a logical problem since Jewish culture in Prague had by then been all but extinguished in the Holocaust, the Czechs were living in a command economy (no traveling salesmen), and anybody with a TV was probably a member of the Communist Party. Well, let's just say that Pita's version of Kafka's story is set in an imaginary Czech Republic that could have existed had there never been a WW II!

Every aspect of this production is admirable. Moon's live music is wonderfully evocative and presented in creepy surround. The videography by Ross MacGibbon is arresting even if the pace is too fast and the resolution not pin perfect. The overall style of the video is "rough and ready" and appropriate for experimental theater. All the performers are totally engaged and engaging, and the directing is impressive throughout. So this gets an "A" under our grading standards and is an "A+" for anyone especially interested in contemporary dance or theater.

The Metamorphosis as Allegory of the Holocaust

This review is not quite over. I've explained how subject title well presents on the stage the tone of irony and humor that's apparent in Kafka's text. Pita, Watson, and Day have probably locked up The Metamorphosis Lite in video. But everybody thinks there's more to the story than this. A lot of intellectual gibberish has been put on paper trying to explain a deeper meaning of Kafka tale, but little of this I've read seems worthwhile. But it does seem to me quite obvious that The Metamorphosis is an allegory for the Holocaust that was looming on the horizon as Kafka wrote.

In the allegory, the Samsa family would stand for European culture and Gregor would stand for the fate of the Jews as the Holocaust unfolded. Could Kafka had foreseen what was to come? Every thoughtful Jew in Europe at the time had to be concerned about the future. The Metamorphoses was published in 1915. Kafka died in 1924 about the time Hilter was writing Mein Kampf. The Czech Jews were early victims, and all of Kafka's sisters died in the Holocaust. Kafka's close friend Max Brod only narrowly escaped to Palestine.

Here's some of what Grete has to say in the book about Gregor after he frightens the tenants away. "It's got to go . . . that's the only remedy, Father. . . this animal persecutes us, dries away our lodgers, and obviously wants to take over the whole apartment and make us sleep in the street." Sounds like the Lebensraum pitch to me. And isn't what Grete calls for exactly what happened in the Holocaust? First the victims were labeled as vermin, then as aggressors, and finally condemned as people who had to go. Some were smart and lucky enough to leave early. But once WW II broke out with the invasion of Poland, there was no more going, but only extermination.

Kafka didn't invent any of this (nor did Hitler). It was already being espoused before and during Kafka's lifetime by radical right politicians all over Europe as part of the anti-Semitic atmosphere of the time. (Our very own Richard Wagner was part of this; he died in 1883, the year Kakfa was born.) Kafka was well-aware of every aspect of the anti-Semitic challenge and the debate between the assimilation Jews and the Zionists. Kafka carefully establishes in the text that the Samsa family were Christians. When Gregor was revealed to be an ungeheures Ungeziefer, it was only a matter of time before the family was ready to call in the exterminators. It seems inconceivable to me that Kafka did not have an allegorical message in mind when he published his story.

The allegory still holds up. [Update Dec. 2023]. After the Holocaust, the Jews created a new county. But the fight for Lebensraum continues. This time the Jews are targeted by some of the closest cousins they have culturally, linguistically, and ethnically. And this time, the Jews are fighting back. They are fighting so ferociously that they run the risk of being seen as the new exterminators with their own version of an Entlösung. And recently Donald Trump, campaigning for President of the United States again, promised his followers to be their “retribution” and to exterminate the “vermin” who are “polluting the blood” of our country.

This website is not about politics or current affairs. One day there will be a dance-theater or other stage presentation of The Metamorphosis Heavy. For now I leave you with this quote from author Stefan Merrill Block: “When you're telling the saddest stories, that's when you need humor the most.”

Here's a clip:

[Additional credits for Performance Filming reported on the video: Stage Manager was Ian Taylor. Deputy Stage Manager was Aisling Fitzgerald. Assistant Stage Manager was Samantha Woollard. Music Mix by Mark Thackeray. Broadcast Consultants were Andrew Bracewell and Peter Byram. Lighting Director was Mike Le Fevre. Vision Engineer was David Griffiths. Camera Supervisor was David Gopsill. Camera Operators were Dave Brice, James Day, Paul Freeman, Tony Freeman, Rob Sargent, and Colin Whipday. Colourist was Alan Bishop. Editor was Steve Eveleigh. Script Supervisor was Yvonne Craven. Production co-ordinator was Beth Murphy. Production Manager was Sarah Hull. Executive Producer was Tony Followell.

Extra features directed and edited by Paul Wu. Camera by SteveStanden. Sound by Paul Parsons.

Design authoring and encoding by WLP Ltd. Packaging design by Jeremy Tilston for WLP Ltd. Cover photo by Alastair Muir. Packaging and booklet photos by ROH/Tristram Kenton. Liner notes by William Richmond. Translations to French by Noémie Gatzler; to German by Christiane Frobenius. BD Producer was James Whitbourn; BD Executive Producerwas Ben Pateman.]

OR