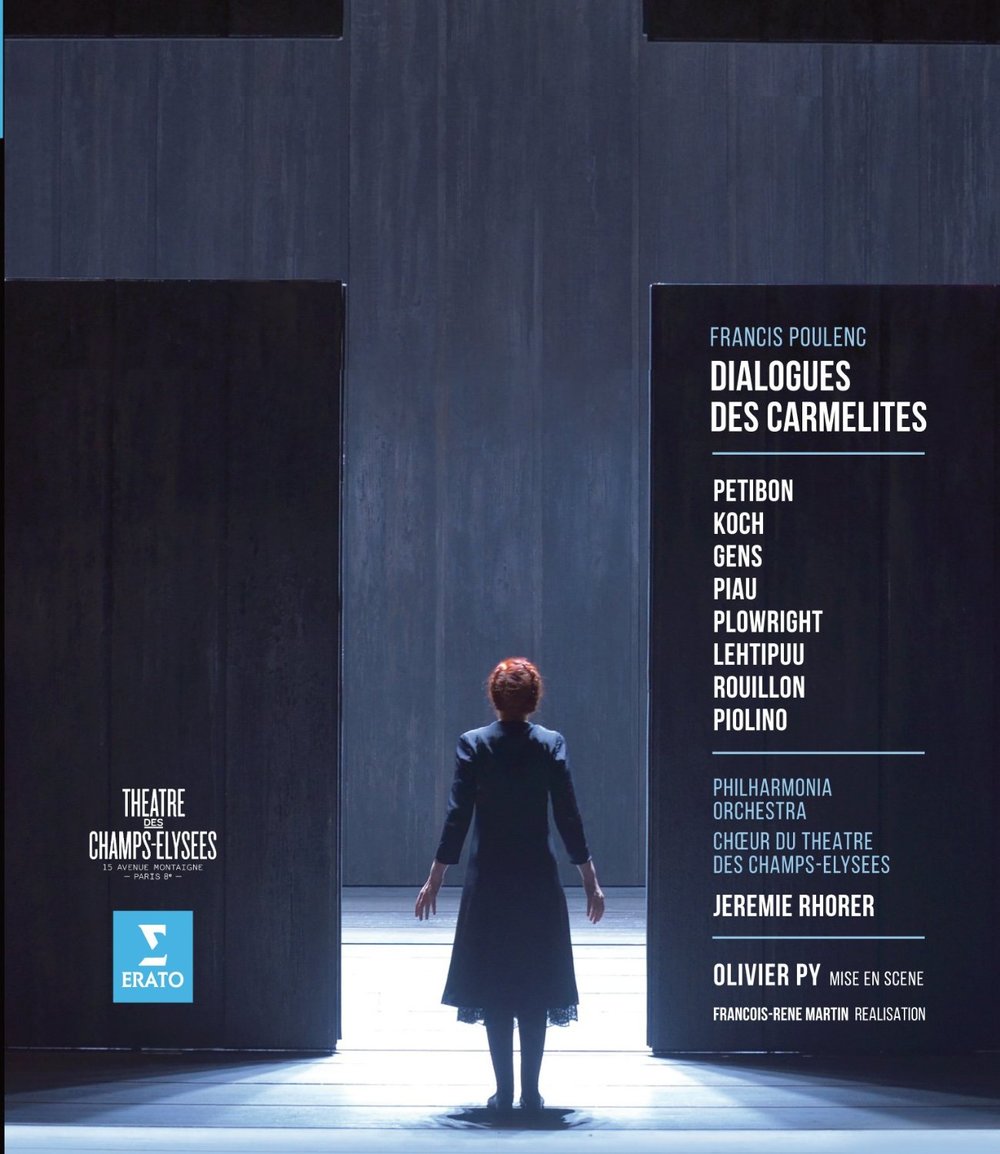

💓 Francis Poulenc Dialogues des carmélites opera to a libretto by the composer. Directed 2013 by Olivier Py at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Stars Patricia Petibon (Blanche de La Force), Sophie Koch (Mère Marie de l’Incarnation), Véronique Gens (Madame Lidoine), Sandrine Piau (Soeur Constance de Saint Denis), Rosalind Plowright (Madame de Croissy), Topi Lehtipuu (Le Chevalier de La Force), Phillippe Rouillon (Le Marquis de La Force), François Piolino (Le Père confesseur du couvent), Annie Vavrille (Mère Jeanne de l’Enfant Jésus), Sophie Pondjiclis (Soeur Mathilde), Matthieu Lécroart (Thierry, le médecin, le geôlier), Yuri Kissin (Le second commissaire, un officier), and Jérémy Duffau (Le premier commissaire). Chœur des Carmélites: Caroline Allonzo, Solange Añorga, Elizabeth Bartin, Anne-Lou Bissières, Béatrice Dupuy, Anne-Sophie Durand, Carolina Fèvre, Claire Geoffroy-Dechaume, Laure Slabiak, Sophie Van de Woestyne, and Mayuko Yasuda. Jérémie Rhorer conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra & Chœur du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées (Chef de chœur Alexandre Piquion). Set design and costumes by Pierre-André Weitz; lighting by Bertrand Killy. Directed for TV by François-Rene Martin. Sung in French. Released 2014, disc has Dolby 5.1 sound. Grade: A+

On July 17, 1794, 16 members of the Carmel of Campiègne were guillotined in Paris by the French Revolutionary government. The true facts of this event are considerably more complicated than indicated by the story of the opera we now review, the Dialogues des carmélites. Thousands of priests, nuns, and other Catholics were killed during the Great Terror including even larger groups of nuns in other parts of France. Amazingly, two of the Campiègne martyrs were civilian employees who stayed with their employers, three were lay sisters, and one was a novice. The group had several years of stressful living during which any of them could have saved their lives. If I understand the theology involved, it would be a sin to seek martyrdom (just a dramatic way to commit suicide). But they were allowed to refuse to disband their association: it would then be up to God to determine to consequences. A few members returned to their families. But for many months the 16 renewed their vows each day, hoping to save their country and church by facing down the Revolution, which was becoming increasingly violent and unstable. When God called them for the ultimate sacrifice, they were ready. They were transported in carts to what is now the Place de la Nation wearing their forbidden habits (because their civilian clothes had been taken to the laundry). They renewed their vows and continued singing as each mounted the scaffold. The civilian employees went first to the machine, then the lay sisters, then the novice, and the Prioress was the last to die. This event must have sent a huge shock wave over all France. Ten day later, Robespierre was himself guillotined and the Great Terror was over.

There should have been 17 Carmel martyrs. Marie de l'Incarnation was the leader in taking the vow, but she was away on Church business when her sisters were condemned. Her superiors ordered her not to return. Later she wrote a detailed account of the true story which eventually led to the beatification of the 16 who died.

Dialogues des carmélites is only roughly based on true events. But all the words of the libretto are precious because they come down to us from a nun who was an eye-witness thru the auspices of 3 artistic geniuses. More about that later. We have a wonderful resource to tell us more about the Carmélites and this opera. Consult the deep, detailed, and readable thesis published in 2010 by musician Gail Elizabeth Lowther called A Historical, Literary, and Musical Analysis of Francis Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmélites.

Dialogues des carmélites personalizes the story of the Carmel martyrdom through a fictional character called Blanche de la Force. Blanche, a member of the French aristocracy, was created as the alter ego of the German woman of letters, Gertrude von Le Fort, who published in 1931 a popular novel called Die Letzte am Schafott (Last on the Scaffold). Below we meet Blanche's father, the Marquis de la Force (Phillippe Rouillon), and her brother, the Chevalier de la Force (Topi Lehtipuu). They are worried about Blanche:

Blanche (Patricia Petibon) suffers from a pathological fear of life. She is also intensely religious. For her, every night is a terrifying replay:

In the two images above you will note the bare electric light on a slender stand. Py and Killy use this odd prop several times on the frequently dark stage. This is appropriate for an opera that is usually presented as a psychological rather than an historical drama, but it must have caused fits for video director François-Rene Martin. Below we see Blanche declare her decision to become a nun ("him" should be "Him"):

Blanche applies for admission to the Carmelite order. The old and terminally ill Prioress, Madame de Croissy (Rosalind Plowright) sees Blanche as a poor candidate:

Mme Croissy explains that the Order is not place of mortification, enforced virtue, or refuge. The sisters must be strong to support the Order: the Order does not support them:

Still, Croissy takes pity on Blanche and decides to give her a chance:

Blanche makes friends with the other novice, Constance (the real Constance was the only novice martyr). Constance is cheerful, eager, and fearless—the opposite of Blanche:

But Constance upsets Blanche with talk that the two of them will die young together:

Soon Mme Croissy is in agony in the scene below with Mère Marie (Sophie Koch) standing by in the shadows. Here is what Plowright had to say about this scene in an interview reported on the Presto Classical website:

"Mme de Croissy is a special role and one of my all time mezzo favourites. There are not that many cameos of this stature in the world of grand opera. This role has an entire scene requiring both the spectrum of voice and acting in extremity. Perhaps what makes Mme de Croissy so special is that she covers her entire life in this one scene with Mère Marie. She then shows her “Mother” side in her dialogues with Blanche and finally undergoes the most horrifically painful death causing her to act in complete contrast to the sermon she has just given to Blanche and dies blaspheming and writhing in agony. It is a show-stealing scene if there ever was one and can only be done by a true dramatic mezzo. So I was hugely grateful to be chosen and to have this preserved on video. Oliver Py created his drama with the use of lighting, sets and amazing effects— my own scene under Py had me in a bed, vertically attached to the back wall of the stage. This allowed the audience to view me as if they were watching from above, “Like God,” as Py put it. It made the singing easier as I was actually standing as opposed to lying down.”

Below is Py's quote from The Sistine Chapel. Mère Marie is horrified by this because she thinks Croissy is seeking relief from a woman rather than trusting in God. But as we learn later, something else is happening here as Croissy and Blanche touch hands:

The death of Croissy:

Gertrude von Le Fort heavily modified the true martyrdom story because she was an artist and philosopher rather than a historian. Le Fort wrote her novel in 1931 and used the story from 1794 to urge her European readers to contemplate the trials and sacrifices looming before them as the titanic struggle between atavistic fascism and futuristic communism trapped them all in a pitiless vise. After World War II, the French writer and thinker George Bernanos was asked to write a screen play for a movie version of the Blanche de la Force story. He added so many philosophical and political ideas that the movie producer abandoned the project as unworkable. Bernanos then revised the movie script into a play called the Dialogues des carmélites. The most important new idea added by Bernanos was his concept of the "transfer of grace" or the redemptive power of vicarious suffering. Bernanos died before much came of his play. But when Poulenc read the Dialogues des carmélites, he immediately was enthralled with the idea of doing the impossible: to write a major opera of ideas with no romantic plot element. He started writing his own libretto by radically cutting most of text of the play until he had the essence of the story that could be told in musical form. Bernanos' transfer of grace idea remains the central concept of the opera. It is introduced by Constance in a scene that takes place right after the death of Mme Croissy. Constance speculates that the hard death of Croissy might be intended by God to make the death of someone else easier. Perhaps we die, she opines, for each other. . . :

A new Prioress, Mme Lidoine (Véronique Gens) is elected by the sisters. Lidoine took the soft line that the sisters should deal with the Revolution using prayer as their only weapon. This the sisters preferred over the hard line of Mère Marie that the Revolution offered the nuns an opportunity for martyrdom. But the tension between Lidoine and Mère Marie was far from over. Below the nuns sing with Mère Marie in the lead. Lidoine wears the full black apron and stands with the "choir" nuns:

The Revolution unfolds and danger increases for all Catholic clergy and functionaries. Blanche's brother, who is fleeing France, fails in his attempt to get Blanche to go home:

Blanche is devastated by her fear of the Revolution and her brother's visit. Mère Marie tells her to "be strong":

The Commissioners are hunting down Priests. The Father Confessor to the convent (François Piolino) narrowly escapes a patrol and takes refuge briefly with the nuns. The nuns want him to stay, but he refuses:

Commissioners order the nuns to disband while Lidoine is in Paris. This gives Mère Marie opportunity to take the lead again in favor of confrontation. She reminds a Commissioner:

The Commissioner declares that the people no longer need servants provided by the Church, and this gives Mère Marie the opening she needs:

Now the convent has been vandalized and desecrated:

Mère Marie proposes:

The Father Confessor supports Mère Marie. A secret vote is taken, and the sisters will take the vow only if all agree. Below you can see Blanche vote "No." Constance knows that Blanche has voted "No". Constance immediately states that she, Constance, cast the "No" vote, but wants to change her mind. Constance does this to protect Blanche from being accused of cowardice. This also gives Blanche the option of leaving the convent or changing her mind. Blanche, still consumed by fear, abandons the Order:

The authorities are closing in. Below are scenes from the final worship services of the sisters. The first scene is, of course, a quote from the Leonardo da Vinci Last Supper mural with Constance at the center taking the role of Christ:

When the sisters persist in meeting together, they are arrested and taken to a prison in Paris. As mentioned earlier, this time Mère Marie was away on business. The prosecutor reads to them a decree of the Revolutionary Tribunal that they are condemned to death:

Poulenc has the sisters singing the Salve Regina (the last prayer in the Catholic Rosary) on the way to the guillotine. Here are the words in Latin with an English translation:

Salve, Regina, Mater misericordiæ,

vita, dulcedo, et spes nostra, salve.

Ad te clamamus exsules filii Hevæ,

Ad te suspiramus, gementes et flentes

in hac lacrimarum valle.

Eia, ergo, advocata nostra, illos tuos

misericordes oculos ad nos converte;

Et Jesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui,

nobis post hoc exsilium ostende.

O clemens, O pia, O dulcis Virgo Maria.

Hail, holy Queen, Mother of Mercy,

Hail our life, our sweetness and our hope.

To thee do we cry,

Poor banished children of Eve;

To thee do we send forth our sighs,

Mourning and weeping in this vale of tears.

Turn then, most gracious advocate,

Thine eyes of mercy toward us;

And after this our exile,

Show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

O clement, O loving,

O sweet Virgin Mary.

The Dialogues des carmélites is the only score I know that includes a guillotine in the percussion section. Each time the blade falls, one of the sisters turns and exits through the stars behind:

In history, Constance died early. Here it appears she will be the last to die. But now she smiles because she sees Blanche coming through the mob to join her. The transfer of grace from Mme Croissy to Blanche has helped Blanche conquer her fears:

Mme Croissy died hard instead of Blanche. Now Blanche is surprised to she that she has the courage to follow her sisters:

Dialogues des carmélites premiered in 1957 at the height of the Cold War. It has been the most successful 20th century opera for several reasons. First, its themes of fear and grace resonate in our time when there has been plenty of fear but little grace. Many lines in the libretto are packed both with a primary meaning plus connotations, philosophical overtones, and literary devices like foreshadowing and irony. Every time I watch this, I discover new things in the words. The musical voice here is exactly the same as that in the LP recording I loved so much as a youth of the Poulenc Concerto for Organ, Timpani, and Strings (Poulenc's first religious work, published the year I was born). Poulenc is so strange and utterly French, but so easy to approach! And with the Dialogues, every musical statement matches perfectly with the text. There were no rancorous disputes between the composer and the librettist as everything was poured out from the same heart.

According to Plowright, Py lined up his all-French core dream cast of Petibon, Koch, Gens, and Piau before committing to proceed. The rest of the singers are equally distinguished and perfectly cast. The stage choir, offstage chorus, and orchestra are all magnificent directed by the unbelievably young-looking conductor Jérémie Rhorer.

As Rosalind Plowright pointed out in her interview, Py provides many beautiful scenes and effects, and you can tell this from the screenshots. But even more impressive that that is the excellent personal directing of the actor-singers, which you can appreciate only by watching the video. The sound engineers did a fine job. The recording of the voices and the orchestra are exquisitely close, well-balanced, and satisfying. Picture quality on my calibrated display is excellent when you consider how little light the TV director had to work with in many scenes.

In May 2020 we have 3 HDVD versions of Dialogues des Carmélites, and subject title is distinctly the best of this group. But by reading my reviews of the competition, you can learn more about this powerful opera. Grade: A+

The Erato trailer gives you some idea about the magnificence of the music:

OR